‘We all deserve representation’: hijab-wearing model Halima Aden on the power of fashion

The first model to wear a hijab on the cover of Vogue, the first to wear a burkini in Sports Illustrated… Halima Aden is used to breaking barriers. Here she talks about shattering stereotypes and using fashion as a force for change

The first model to wear a hijab on the cover of Vogue, the first to wear a burkini in Sports Illustrated… Halima Aden is used to breaking barriers. Here she talks about shattering stereotypes and using fashion as a force for change

Halima Aden, then aged 19, became the first contestant in the Miss USA 2016 beauty pageant to wear a hijab and burkini, attracting the attention of French fashion legend Carine Roitfeld. The following year she became the first hijab-wearing model to sign with a global modelling agency, IMG, and then the first to walk at New York fashion week, for Yeezy, the Kanye West brand. She later became the first hijab-wearing model to make the cover of Vogue – twice (first Vogue Arabia, then British Vogue) – and soon afterwards a Sports Illustrated swimsuit shoot followed. By that point she’d already become a Unicef ambassador, and a go-to voice on diversity in the fashion industry. In 2017 she gave the first TED talk at a refugee camp in Kakuma, Kenya. Teen Vogue went with her.

When we meet, at a hotel near King’s Cross, I ask if it ever gets tiring, being the first in so many different ways, shouldering the burden of representation. “Somebody needs to,” Aden says. “I want my sister, my little nieces, even my nephews to see representations of somebody who wears a hijab in modern ways, in such a way that they can relate to.” We’re sitting side by side on a window seat, Aden holding court before a little audience of PRs, management and her best friend, Lizeth, who has travelled with her from the US. Though she looks very much the high-fashion figure, all in black – sequins and brocade lace, knee-high stiletto boots – she seems younger than her 22 years, gabbing away in the stream-of-conscious slang and asides of a teenager still starstruck by the turns her life has taken.

But on the topics of diversity, representation and sustainability, she speaks with passion and conviction. She has said in the past that, growing up in the US: “The only times I saw somebody dressed like me was on CNN – and they weren’t doing anything I approve of.”

“I feel like we all deserve representation and I didn’t have that,” Aden says now. “I never got to flip through a magazine and see somebody who looks like me.” Lizeth digs out the latest issue of Essence magazine, Aden proud in pink on the cover. Aden takes it from her, somewhat wonderingly. “Sometimes it’s so wild for me,” she says. “I still catch myself… When my friend went and got that from the newsstand, I was like: ‘Oh my God.’”

Aden now has her own 47-piece hijab collection, Halima x Modanisa, and her hijab is stipulated as non-negotiable in her contract with IMG. “It’s a big part of my identity,” she says. “It’s not because I don’t think people are going to listen – it’s more so they know what to expect. I always bring extras – my own set of turbans, turtlenecks, tights – because it’s a collaboration. I also recognise that for a lot of people, in my first year especially, I was the only hijab-wearing girl they’d worked with. So they’re not going to necessarily know 100% what to expect, just like I didn’t know what to expect with fashion, because it’s not the world that I come from.”

She does have certain requirements, such as a pop-up tent in which to change backstage at shows, but she says she’s never been uncomfortably set apart, or made to feel othered. She remembers her experience of walking for Yeezy at New York fashion week in 2017, her breakout year, as a watershed moment. The first outfit she was presented with “was just not going to work,” she says, gesturing above her knee – too short. “Even then I knew: walking away when something doesn’t fit is always better than feeling you need to force something.”

She returned to her hotel, disappointed but resolute. “And then, without having to say anything, they called back: ‘We have a second option.’ I tried it on and it was perfect. I just knew it was a pivotal moment in my life. The people who you want to work with, they’re willing to work with you just the way you are.”

That same year, Aden remembers walking for MaxMara at Milan fashion week in a look that had been designed with her in mind. When she posted it on Instagram, a woman commented: “He keeps you in mind, he keeps us in mind. Now this Muslim shopper will keep MaxMara in mind.” Aden shared it with the brand. “I was like – wink-wink-wink!”

It led to an exclusive capsule collection in the Middle East, for which Aden was the face. “It’s a win for designers when they’re diverse; it’s a win for the brand, it’s a win for everybody – we all want to see a little piece of ourselves reflecting back.” And it makes a difference, she says. The year after Aden became the first contestant to wear a hijab in Miss USA, there were seven others. Last year she was one of two hijabi models on the MaxMara catwalk in Milan, and one of three for her second Vogue Arabia cover.

When Aden was seven, she used to pray for rain – the kind of torrential rain that would wash away her new home in the American Midwest. “I remember thinking: ‘Then our neighbours could come out and play,’” she says. Even the structure of her apartment building felt alienating. “I was like, ‘God, everybody is so isolated.’”

Aden was born a refugee in the United Nations Kakuma camp in northwestern Kenya, where her mother had fled the Somali civil war in 1994. There their house was made of mud, scraps, sticks – anything her mother could find. “It would be normal for me to go to nursery school, come back and find it had washed away,” she says. But then the community would come together to rebuild it, “and then it’s the kids’ time to play around.”

The model remembers her childhood in the camp as being joyful and supportive. “There’s no walls keeping you apart from your neighbour,” she says. In her new home in Missouri, where she was relocated with her family in 2004, before moving to Minnesota, where they live today, the barriers stood strong.

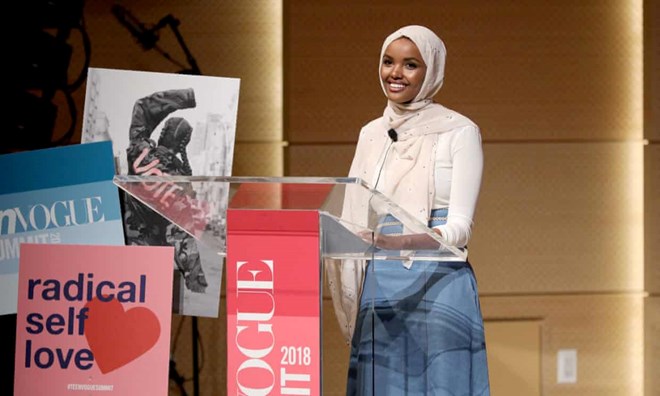

Photograph: Cindy Ord/Getty Images

“Kakuma” translates from Swahili as “middle of nowhere”. “Sometimes, when I’m like, ‘I was born in the middle of nowhere,’ people think I’m joking,” Aden says. “But if you actually look at Google Maps…” People tend to think of a refugee camp as being a temporary settlement. But Kakuma is “more of a city of its own,” says Aden, in both permanence and size. Established by the UN in 1992 with a 70,000-person capacity, it has since ballooned to about 192,000 registered refugees and asylum seekers, the vast majority of whom are never resettled (the global figure is less than 1%).

As a child, Aden remembers thriving under the collective care of the community, which was two thirds women and children. She was bright – she spoke Somali and Swahili, sometimes translating for the grown-ups – and popular, roaming the camp with up to 30 playmates of mixed ages and ethnicities. (“If you could keep up, you were in the group.”)

Aden is well aware that her happy stories of childhood challenge the stereotype of the “tragic refugee”, though she credits her mother with working hard to shield her young family from hardship. Aden never knew her father. He was lost during the Somali civil war, and assumed dead by her mother; he made contact after they had moved to the US, but died before Aden could develop a relationship. “It was both the scars and the smiles,” she says. “It was a happy childhood and also, we lived in uncertainty.”

Symbolic of this limbo was a noticeboard that was updated with the names and destinations of those lucky few bound for resettlement. Aden remembers it as larger than life, “like something out of The Hunger Games”: “It would control your entire future – it was literally the difference between life and death. For parents it meant a brand new life: ‘We’re starting over, we won the lottery.’ But for the kids it is: ‘I’m never seeing my friends again’.”

Another common misconception of being a refugee, Aden says, “is that you get a say where you go”. Her family were relocated to a poverty-stricken, crime-rife neighbourhood in St Louis, Missouri, which – compared to the “nurturing” community of Kakuma – came as a shock. That was when she felt most isolated, when she wished for her house to wash away. It was the first time she’d heard gunshots. “But nonetheless, did I have the fear of malaria? No – so, in a way, it was like trading one obstacle for another.”

The biggest hurdle was learning English: Aden’s school in St Louis did not have an English language programme. After two weeks of presenteeism, Aden recalls her mother asking her to read some written English aloud. “I literally started mouthing the words to Dilemma” – rapper Nelly and Kelly Rowland’s syrupy duet, which she knew from the radio. Aden mimics a haltering recital: “‘No matt-er. Whatido. All I think about. Is you’ – I just couldn’t stand the idea of disappointing her.”

Eventually Aden’s mother decided to relocate the family to St Cloud, Minnesota, where they found a community like the one that they had left at the camp. At first they were heavily reliant on it, living on food stamps and even, for six months, in a women’s shelter. Aden remembers the kindness of neighbours, taking the family to the grocery store during the punishing winters, giving her mother lifts when she couldn’t drive. “It’s why I’m so loyal,” she says. “I love my state.” She lives in St Paul now, closer to the airport, but only 40 minutes from her mother, who’s still in St Cloud. Minnesota is known for high taxes, but Aden says she is happy to pay them. “I relied on welfare when I was little… I think of it as my way of paying back.”

Before we meet, Aden’s team is adamant that I don’t ask her about Trump or US politics, so instead I ask her how superficial diversity in fashion tallies with a more fractious, divided world.

“I don’t even really avoid politics,” she says, “but it’s not something that I’ve needed in order to connect with people. Once I share my story, there’s always some common ground. It doesn’t have to be: ‘I grew up in a refugee camp.’ I get just as many messages, believe it or not, from parents who are not Muslim, who are not black, who say, ‘Thank you for making modesty look cool and young’.”

When she entered the Miss Minnesota USA pageant in 2016, as a freshman at St Cloud State University, Aden told local media that she wanted to represent Muslim women and counter the image that they were oppressed. “The hijab is a symbol we wear on our heads,” she said. “But I want people to know that it is my choice.” Today she says her motivations for entering were less lofty. “College tuition is expensive in the States, muuuuuucho expensive!” And the top 15 at the pageant were offered scholarships. Did Aden think she’d win? “No, God, no.” She laughs. “But top 15? I was like, ‘I think I could do that’.”

‘I want people to see me wearing a hijab in ways they can relate to’: Halima Aden wears jacket, shirt and trousers, all by stellamccartney.com; trainers by Good News, net-a-porter.com; bag and brooches by bottletop.com; and headscarf by Halima x Modanisa, modanisa.com. Photograph: Jean-Paul Pietrus/The Observer

Aden’s mother was strongly against her entering the pageant, arguing it would distract from her studies, and that the two-piece burkini was too skimpy. Though they have since been able to find common ground through her advocacy and work with Unicef, it can feel like they are from two different cultures sometimes. She didn’t tell her mum about the Sports Illustrated shoot “until it hit newsstands”.

She was also criticised by members of the Muslim community who saw modelling as haram – forbidden by Islamic law. “It was scary to put myself out there, because I didn’t know if I would get backlash, or how bad it was going to be,” she says. Two days before the pageant, Aden almost pulled out. But as she told the newspaper at the time: “You don’t let being the first to do it stop you.”

She ended up making the semi-finals, “braces and all. And then IMG came calling – like, ‘Well, well, well… maybe I don’t need school.’” She leans back, for a second jokily triumphant – then seems to feel a chill coming in from across the Atlantic. “I’m kidding. Sorry, Mom!”

The global spotlight on Aden caught the eye of Carine Roitfeld, who flew her to New York to shoot the cover of CR Fashion Book with Gigi Hadid, Paris Jackson and legendary photographer Mario Sorrenti. Aden agonised about asking for a selfie with Gigi (“So cringy,” she says now). As for Sorrenti, though, she had to Google her later.

His direction to her was, “Give me sexy”, she seems a little abashed to say. “I didn’t know fashion lingo, I didn’t know photographers. I’m a Minnesota girl – very small town.” Even after signing with IMG, she watched all of Tyra Banks’s outlandish reality series America’s Next Top Model “to practise”. Seven months into her modelling career, she was still working part-time as a housekeeper in St Cloud.

But rather than asking Aden to change, fashion’s royalty has made room for her as she is. Last week she was back in Kenya for a shoot and “I was just thinking, how crazy is it that, in one lifetime, I’ve gotten to experience both extremes.” Aden says she does not feel angry about the inequality she has seen – partly because she does not find it to be productive. “It’s like when I say: ‘We don’t want your pity.’ Let’s talk about solutions, invite refugees to the table. They’re part of the conversation – no policies should be enacted without their say.”

Though she rules out a career in politics (“for now”), in the future she hopes to return to Kakuma with Unicef to inspire hope within the camp for a new life beyond it. “I couldn’t tell you what that would have meant to me as a six or seven-year-old – like, ‘Wait, there’s a life outside these walls?’ Hopefully, it’s not going to be so rare to see kids from the camps grow up and become teachers, lawmakers, presidents and CEOs of Fortune 500 companies. There’s talent everywhere.”

For now Aden is pursuing opportunities in “fashion activism”. This month she was announced as the new face of the British accessories brand Bottletop, which was ahead of its time in positioning itself as “sustainable luxury” in 2002. Its handbags and clutches, which are made from sustainable leather and upcycled metal ring pulls, help to alleviate poverty in Brazil, Nepal and Kenya. Aden is optimistic in general, but particularly about the potential for consumer choice to be a force for positive change: “I think we’re at a place where people want to support brands and organisations they know are giving back.” She is also an ambassador for Bottletop’s #Togetherband campaign, which is tasked with raising awareness of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Aden is probably one of the few celebrities who can “relate personally” to all 17 of them. She has been assigned the eighth goal: “Decent work and economic growth.” The fact that the Swiss multinational bank UBS is a founding partner seems to suggest which way the wind is blowing.

“My career in fashion is not just, ‘I want to work with this brand, I want to get on that catwalk’ – we’re not sitting here talking about ‘Buy this heel, because this heel will make you feel sexy.’” She kicks up her stiletto boot, knee-high in black patent leather (admittedly very sexy). “I’m proud that I can say I combined fashion and activism. I can’t do one without the other.”

Aden sees that her story, from refugee camp to the cover of Vogue, is an unusual one. But she has had to navigate it herself – down to mentioning, at her very first meeting with IMG as a teenager in New York, that she would like to work with Unicef. “I had to learn, in the beginning especially, that maybe I’d never find another model who I could relate to. But I’m making my own path, and it works perfectly for me.”